“At that time the Feast of Dedication took place at Jerusalem” (John 10:22).

Chanukah (Festival of Lights) is a celebration of events that occurred during the Intertestamental Period—the four hundred years known as the Silent Years between the closing of the Old and the dawning of the New. Though it isn’t actually recorded in Scripture, its history is very important, laying the groundwork for the New Testament age. This year Chanukah begins on Sunday, December 18th, and ends on Monday, the 26th. This annual feast is not one of the three biblical feasts of Passover, Feast of Weeks (Pentecost), and Feast of Tabernacles, which God commanded Israel to observe.

Today, Jews all over the world still celebrate this feast, but it is popularly known by its more modern name, Chanukah, or the Festival of Lights. It is celebrated by Jews in the traditional way of lighting the eight lights of the Chanukah Menorah. Why do Jews all over the world in early December light these funny-looking lampstands? Where did this tradition originate? What does it mean? To understand this, we must go back over two thousand years.

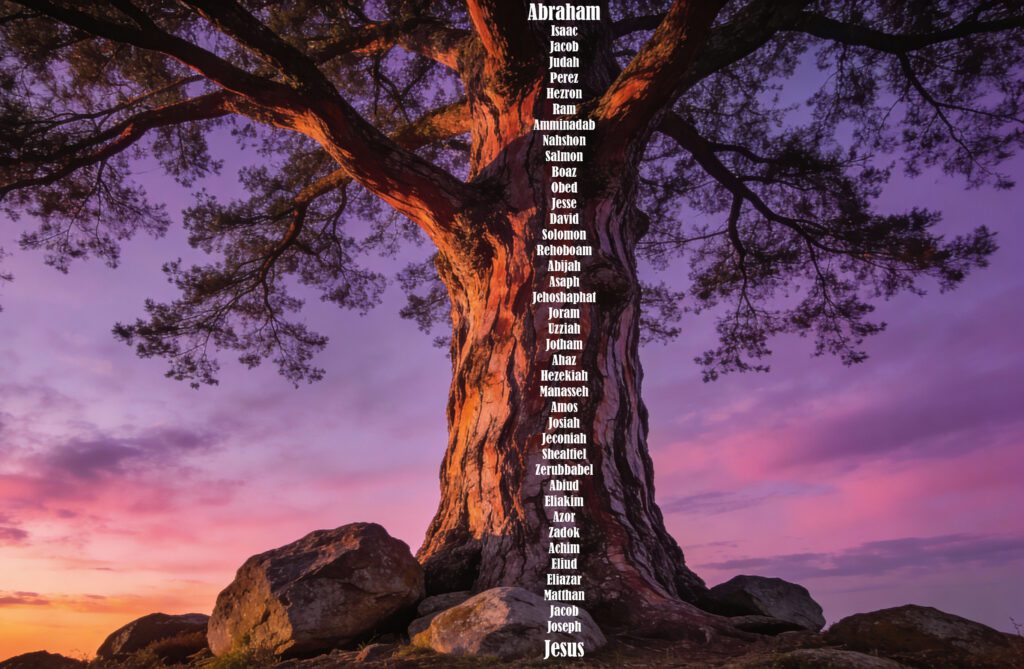

You will remember that the Old Testament closes with the story of the Jewish people going into captivity in Babylon. Jeremiah prophesied that their captivity would be for seventy years (Jeremiah 25:11). Afterwards, God told them that they would return to the land and rebuild the temple of God. One Jew carried into Babylon was a young man from the tribe of Judah named Daniel. God raised up Daniel in Babylon as a mighty prophet. His prophecies are some of the most important in Scripture. God showed Daniel that the Jewish people would live under four successive Gentile world powers (see Daniel Chapter two). The first was Babylon (which they were already living in), followed by a second kingdom, the Kingdom of the Medes and Persians (Daniel lived into that period). It would be under the Persian king Cyrus that God would issue the decree for the Jews to return and rebuild the temple.

Then Daniel saw a third kingdom the Jews would live under, the Grecian Empire. In Daniel chapter 11, he sees a mighty king that would emerge during this third kingdom who would “rule with great power and do as he pleases” This is clearly Alexander the Great, who spread Hellenistic culture throughout the world. After him, his kingdom would be divided between four empires (which was what happened when Alexander’s kingdom was divided between his 4 generals). One of those generals was Seleucus, from whom a people called the Seleucids emerged. At that time, the Jewish people became pawns between the two kingdoms of the Seleucids and the Ptolemys (Egypt).

The story that led up to Chanukah starts with Antiochus III, the King of Syria, who reigned from 222-186 B.C.E. He had waged war with King Ptolemy of Egypt over the possession of the Land of Israel. Antiochus III was victorious, and the Land of Israel was annexed to his empire. At the beginning of his reign, he was favorably disposed toward the Jews and accorded them some privileges. Later on, however, when he was beaten by the Romans and compelled to pay heavy taxes, the burden fell upon the various peoples of his empire, who were forced to furnish the heavy gold that was required of him by the Romans. When Antiochus died, his son Seleucus III took over and further oppressed the Jews. He only reigned for a short while, and then his son took the throne, Antiochus IV. He was a tyrant of a rash and impetuous nature, contemptuous of religion and of the feelings of others. He was called “Epiphanes,” meaning “the gods’ beloved.” Several of the Syrian rulers received similar titles. But a historian of his time, Polybius, gave him the epithet Epimanes (“madman”), a title more suitable to the character of this harsh and cruel king.

Desiring to unify his kingdom through the medium of a common religion and culture, Antiochus tried to root out the individualism of the Jews by suppressing all the Jewish Laws. He removed the righteous High Priest, Yochanan, from the Temple in Jerusalem and, in his place, installed Yochanan’s brother Joshua, who loved to call himself by the Greek name of Jason. (For he was a member of the Hellenist party, and he used his high office to spread more and more of the Greek customs among the priesthood). A rumor spread in Jerusalem that Antiochus had been killed. When Antiochus returned from a successful war in Egypt, he heard about this rumor and ordered his soldiers to fall upon the Jews. Thousands of Jews were killed, and he enacted a series of harsh decrees against them. He demanded that all copies of the Scriptures be destroyed; Jews were forced to eat unkosher food and prohibited from keeping the Sabbath. Circumcision and the dietary laws were prohibited under the penalty of death. Later, he entered Jerusalem, destroyed a large part of it, and slaughtered men, women, and children. His crowning act was to enter the Temple of God take away the golden altar, candlestick, and vessels, and other treasures. He then set an idol statue of Jupiter in the Holiest of All and commanded the Jews to worship it. He also sacrificed swine to the Greek God Jupiter in the Holiest of All and forbade any Jewish rites like circumcision and the Sabbath to be practiced.

There is a famous story of Rabbi Eliezer, who, at the age of 90, was ordered to eat pork. When he refused, he was told to just put it up to his lips and pretend to be eating it. Still, he refused and was killed. Antiochus then sent his soldiers from town to town, ordering Jews to worship statues and pagan gods. It was during that time that his soldiers came to the town of Modin, where an aged priest named Mattiyahu lived. They erected an altar there in the marketplace and ordered Mattiyahu to offer sacrifices to Greek gods. Another Jew stepped up to the altar to offer the sacrifice, and Mattiyahu grabbed his sword and killed him. Then he and his sons and their friends turned on the Syrian officers and men and killed them. Mattiyahu knew that when Antiochus heard of this, he would send his troops and punish them. He left Modin with his sons and friends and hid in the caves of Judea.

Many loyal and courageous Jews followed them. They formed legions and began to plan assaults on the Syrian army. After they struck them, they would go and hide in the caves before their enemies could regroup. When Mattiyahu died, his son Judah became the leader of this band. He was nicknamed Macabeee, a word meaning ‘hammer’ because he was a fierce warrior. Under Judah Macabee, the Jewish people vanquished the Syrians. After a while, Judah and his band would not just fight the Syrians and then hide. but would fight them out in the open. The goal of Judah was to go to Jerusalem and reclaim the temple. Finally, in B.C. 164, the Syrians were driven from Jerusalem. Judas Maccabees and his band cleansed the Temple from the profanations to which it had been subjected.

This cleansing of the Temple occurred on the 25th day of Chisleu (December 25th) and lasted for eight days. When it was completed, they wanted to light the Menorah, the Golden Lampstand that stood in the temple. They wanted to light the eternal light in the temple, but the problem was that Antiochus had melted it down and used the gold, so it no longer existed. Tradition says that Judah took the golden-tipped spears of his enemies and melted them down to have gold to build a menorah for the temple. Then they had a real problem. Only special oil could be used to light the lamp. If there were none of it in the temple, they had to make it from scratch, and that would take eight days. They searched through the temple and found only one vat of consecrated oil which would only last for one day. Now they faced a real dilemma; should they light it and then let it go out while they made new oil (which would take eight days), or should they not light it and therefore hold off consecrating the temple for eight days? They decided to light the menorah and then prepare the new oil. But then a miracle occurred: they lit the menorah, and though it only had enough oil to burn for one day, it burned for eight days.

This feast was hereafter known by the Jewish people as “The Feast of Dedication.” According to John’s Gospel, Jesus Himself kept the feast in Jerusalem (see John 10:22). It was celebrated each year in early winter as the time when the temple in Jerusalem was rededicated. Eventually, it became known as the ‘Festival of Lights.” Each Jewish family would take a replica of the temple menorah, also known as the chanukiya, and light a candle for eight days to commemorate the miracle of the oil back in the time of the Maccabees.

The Menorah actually has nine lights because the middle light is called the Shamash, and it is used to light the other eight candles. Each night we light the candle at the right end of the menorah. We do this for eight nights until all of the candles are lit. Tradition says that the Hanukah lights should burn for half an hour after nightfall. Jews were commanded to put the Menorah in a front window or by a doorway so all would see it.

0 Comments