Blessed is the man

who walks not in the counsel of the wicked,

nor stands in the way of sinners,

nor sits in the seat of scoffers;

but his delight is in the law of the Lord,

and on his law he meditates day and night.

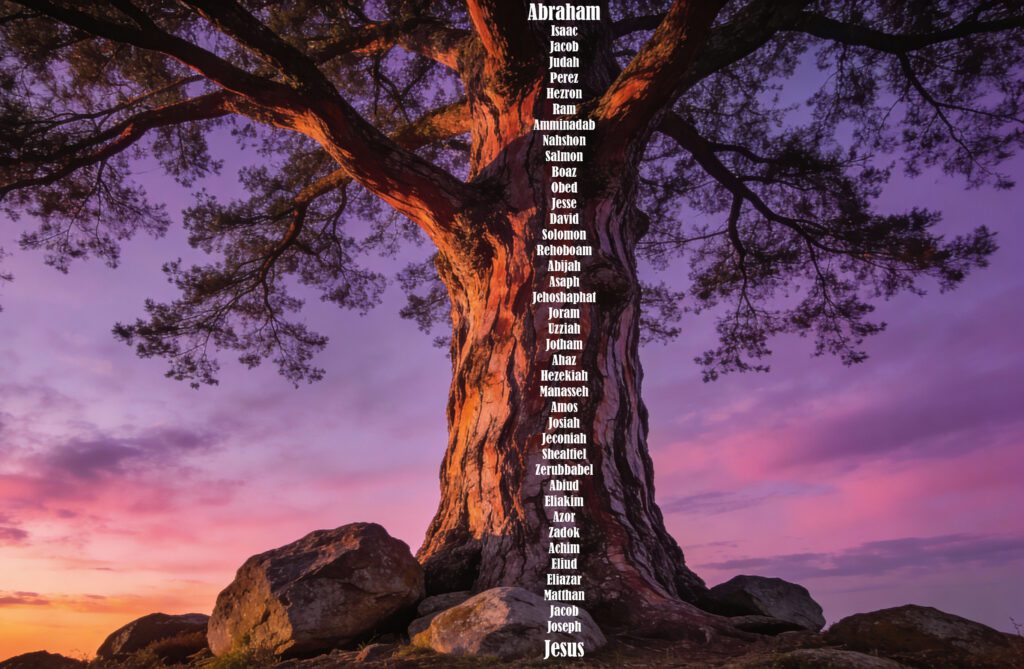

He is like a tree

planted by streams of water

that yields its fruit in its season,

and its leaf does not wither.

In all that he does, he prospers.

The wicked are not so,

but are like chaff that the wind drives away.

Therefore the wicked will not stand in the judgment,

nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous;

for the Lord knows the way of the righteous,

but the way of the wicked will perish.

Psalm 1

In the previous blog, we examined Psalm 1 as a sort of introduction to the Psalter. As such, it instructs us about the place meditation should have in effective praying. The righteous man or woman takes great pleasure in God’s Word by meditating on it day and night (1:2). Such meditation serves as a bridge between the study of Scripture and praying.

This Psalm teaches that prayer is really a response to God’s written revelation. Those who have learned to pray effectively have learned how to use God’s written revelation as the basis of their praying. Two examples will demonstrate how powerful this is. In I Kings 17:1, there is a record of Elijah the Tishbite confronting Ahab with these words: “As the Lord, the God of Israel, lives, before whom I stand, there shall be neither dew nor rain these years, except by my word.” While it sounds as if Elijah was speaking prophetically, closer examination reveals that all Elijah was really doing was praying what God had already said in the Torah (five books of Moses). In Leviticus, God told Israel that if they refused to obey Him, He would “make your heavens like iron and your earth like bronze” (Leviticus 26:19). This corresponds to what He also told them in Deuteronomy: “The Lord will make the rain of your land powder. From heaven dust shall come down on you until you are destroyed” (Deuteronomy 28:24).

The same is true in Solomon’s prayer of dedication at the completion of the temple (see I Kings 8). Much of it is merely Solomon reminding the Lord of what he had said he would do for his father, David. Also, much of his prayer at the dedication of the temple is a reiteration of the blessings God promised if Israel obeyed.

These examples (and there are many others) demonstrate clearly how Holy Scripture always informs prayer. This is more than merely quoting the words of Scripture in prayer (though that is certainly acceptable), but deeply meditating on its truth so that when we do pray, the words we use are informed by God’s Word. This is what the statement means that meditation serves as a bridge between studying the Bible and prayer. When we study the Bible, we seek to understand the meaning of a passage through various hermeneutical tools. It is largely an intellectual process; our minds are engaged to the fullest in trying to grasp the redemptive and historical meaning of a passage.

But in meditation, we are allowing the truth of the passage to engage our minds fully on three levels: extracting from the passage what there is to learn about God; allowing the Scripture to teach us what it reveals about ourselves and finally, allowing the Scripture to inform us as to what we should ask God for. Let us look at each of these briefly.

The first thing we should always be aware of is what a text teaches us about God. The Bible is not a book about various things such as redemption, forgiveness, and covenant love, etc., but first and foremost a book about God. Meditating on Scripture is learning all the text teaches us about God Himself. It is then, as we meet God in the text, we can begin to praise and worship Him. This is the goal of all theology; to form a proper understanding of God from a text, so as to offer him acceptable worship. Many people make theological understanding an end in itself. They study a text carefully but never allow the text to bring them to God. That is why there are so many in the Church today who, while possessing good theological concepts, remain strangers to the knowledge of God.

Not only should we meditate on Scripture to learn what we can about God, but also to learn much about ourselves. This is the proper outcome of learning what we can about God from Scripture—to see God as He is to inevitably see ourselves as we are. When Isaiah saw the glory of the Lord in his temple, he cried out “Woe is me; I am lost” (Isaiah 6:5). As we meditate upon Scripture, we should ask what this text has to teach us about our own hearts, being ready to repent if, while meditating, we realize we are not obeying this text. While meditating, we should consider certain things such as: “What difference would it make in my life if I believed and obeyed this passage?

Finally, meditation should guide us as to what we should ask God for. This is essentially what it means to pray in the name of Jesus. Using our Lord’s name at the end of our prayer is not a magical incantation; somehow if we use those words our prayers will always be answered. To pray in Jesus’ name is to base your entire approach to God totally on the work of Christ in redeeming us. But it also means that we pray in accordance to God’s nature and according to his desires. The Psalmist understood this when he declared, “Delight yourself in the Lord and he will give you the desires of your heart” (Psalm 37:4). Those desires are tempered by the fact we are taking delight in Him.

So often, we rush into God’s presence from studying the Bible without giving sufficient time to meditation, bringing to God our list of requests we are asking of him. But what often happens when we meditate first before praying is that God so changes our desires, we find ourselves totally changing what we ask for. At times, we are so overcome by the awesome sight of God we have gained through meditation, we are unable to do anything but worship in his presence. At other times, we can only remain silent before him.

If you have not learned to meditate before praying, I would suggest using the book of Psalms as a starting point. God gave us one hundred and fifty prayers, covering the entire gamut of devotion to God. I have been doing so for many years and have reaped a veritable spiritual feast from this practice.

0 Comments